Above-grade perimeter walls built with concrete masonry units, or CMUs, may only represent about 7% of the new-home construction market nationwide. But in markets across the South, especially Florida, it's the way to build the first floor of almost all homes.

As the federal Energy Star program and International Energy Conservation Code continue to push the envelope for effectively insulating exterior walls against thermal loss to boost a home's energy efficiency, builders of block walls are being forced to adjust their practices to comply with the more stringent standards.

Fortunately, the insulation and air sealing market is maturing along with the codes and standards, providing an increasing number of options for block wall construction. Newer methods, in fact, often combine products to achieve higher levels of thermal resistance, allowing new-home builders and remodelers retrofitting older homes to match or even surpass the efficiency of wood-framed wall assemblies without busting the budget.

"There are a million ways to skin that cat," says Lucas Hamilton, manager of building science application at CertainTeed in Valley Forge, Pa. "Contractors can now let the unique factors of a project dictate a solution."

Best Practice

For a single-level, net-zero energy, LEED-rated new home near Orlando, Fla., housing giant and mainstream green pioneer KB Home exemplified the new-age practice of optimizing various insulation and air-sealing options for CMU perimeter walls.

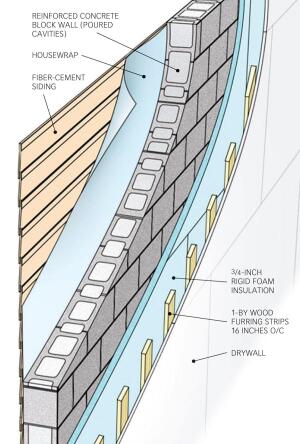

Step 1 called for gluing 3/4-inch thick, rigid foam panels directly to the inside face of the 10-foot high block walls for the roughly 2,700-square-foot home. In addition to their inherent thermal value (about R-6 per inch, comparable to spray-foam products), the rigid foam panels featured a foil face to serve as an air/moisture barrier.

KB Home then applied a compatible flashing tape along all abutting joints to create a monolithic plane to block air and thermal transfer through the CMU walls. After that, the builder fastened 1-by, floor-to-ceiling wood furring strips at 16 inches on center to the foam to serve as nailers for drywall.

But the assembly wasn't done. For the sections of the house designed for fiber-cement lap siding, KB Home secured a housewrap to the exterior face of the CMU walls with an industrial spray adhesive, then bridged all joints with a compatible flashing tape to create an effective air-moisture barrier behind the siding.

Better Practice

Except in markets with seismic or high wind activity, building codes allow structural CMU walls for single-family, single-level homes to be left partially or completely unfilled with grout. A common way to improve the thermal performance of those walls is to fill the cavities with a foam-in-place insulation.

Working from the inside face (or the surface most likely to be covered with a finish), contractors drill 5/8-inch or 7/8-inch holes into the face of the blocks about 4 feet up from the floor to fit an injection tube running from a "mixer" that combines a non-toxic liquid resin, a foaming agent, and air.

Once the foam starts to seep through the injection holes (indicating a full cavity encompassing several blocks), the process is repeated along the length of the wall every 4 feet, and then again along the top of the wall about a foot short of its full height.

This method is popular and mature is markets where CMU walls are prevalent, but it does require an extra contractor and, depending on the scope of the project, an extra few days on the schedule. The insulation also needs about 72 hours to cure before the injection holes can be patched and the walls covered with a finish cladding, but the result is a thermally efficient and somewhat more stable wall assembly.

This method is also something that can be done in a retrofit situation, assuming some or all of the interior or exterior finishes are removed to expose the blocks.

Good Practice

For builders on a tight budget and under little or no pressure from homebuyers or local codes to improve the energy performance of a CMU-built home, a common, low-cost method of construction entails building and insulating a "false wall" along the inside face of the block wall.

Simply, the process calls for framing non-structural 2x4 wall sections secured at the top and bottom plates and one to another, then insulating the cavities with conventional rolls of fiberglass batts.

In cooling climates, specially those prone to high outdoor humidity, a vapor retarder between the porous CMUs and the false wall will help mitigate moisture migration to the framed area, where it could promote mold growth. A housewrap on the outside face can also help manage that issue.

This practice affords a few things, such as a nailing surface for drywall or other interior finish paneling and a concealed chase for wiring and plumbing runs. On the other hand, it takes away square footage from the living space and, to be thermally effective, requires the batts to be properly installed, specifically around any intrusions and without compressing the batts.

The good news for dealers is that most of the materials to satisfy these options are available in inventory or as a special or limited order from conventional distribution sources, and that the methods and materials apply to both new construction and, to a larger extent, the millions of homes in need of an energy retrofit.